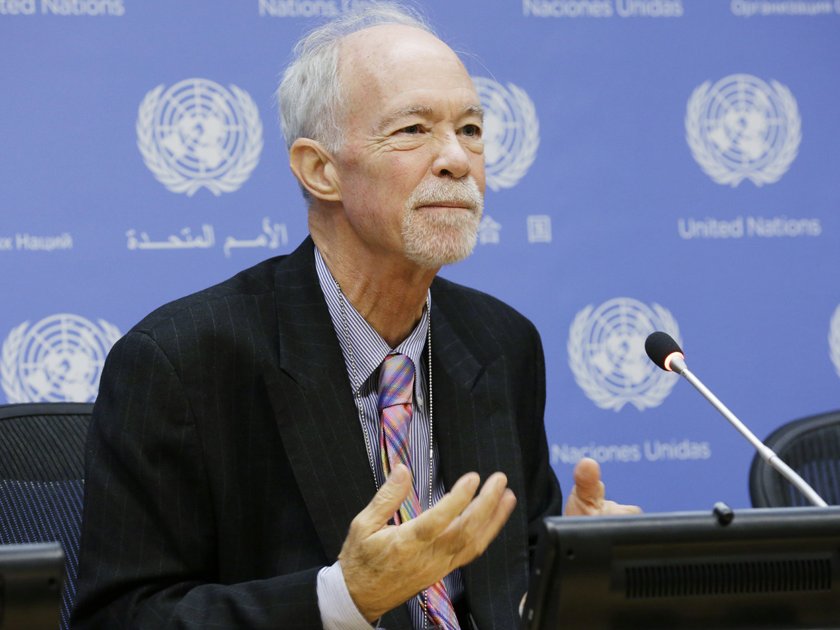

The refugee crisis is a tremendously expensive undertaking for Europe and the repercussions for the United Nations are going to be significant, according to David Malone, Rector of the UN University. He said the UN is not well-prepared for the cut in its budget from Europe that may result from the necessary reallocation of funds.

“There’s a widespread hope that this is just a blip, but I fear that Europe’s internally driven preoccupations will last at least a few years,” Mr. Malone said. “Whether European money then returns to the UN or not is impossible to predict.”

The UN needs to be selective with who it lends its own credibility to, he argued. It needs to engage with the real world, which includes NGOs and civil society, across the board. “The UN lives in a bubble in many ways, and the real world is out there with all sorts of different constituents, good, bad, and indifferent.”

When it comes to how the UN is perceived, he argued that there is a much more positive view in the developing world than in industrialized countries.

“In the industrialized world, there may be reasons for the slightly more negative view and those reasons may be that the UN has been paid for by the industrialized world very largely,” he noted. “Once the developing world starts paying for the UN more than it has in the past, it also may become more critical.”

Mr. Malone spoke to International Peace Institute Senior Adviser Warren Hoge on the margins of ICM’s ninth retreat, on the relationship between the UN and regional organizations, civil society, the private sector, and NGOs, held on November 20-21.

Europe right now is going through a terrible, testing time. Do you see consequences for the United Nation’s leadership in the problems and the test that Europe is passing through now?

Definitely—I think the UN had the luxury for a very long time of taking European generosity for granted. And starting with the economic crisis in 2008, when Europe had to deal with a number of internal problems, it became more internally oriented and driven. In many ways, the problems of the rest of the world faded somewhat for the Europeans. At first there were no practical consequences of this, but with the recent refugee crisis in Europe—which a number of European countries have dealt with generously and magnificently, others somewhat less so—and the arrival of a million-odd refugees this year, it is a tremendously expensive proposition for Europe.

Many European countries have decided with regret, I think, that one of the ways they’re going to fund the integration of refugees is by taxing their development budgets. When you look at the budgets of many of the UN’s development and other agencies, a large part of the funding, one way or the other, comes from European government development budgets. So I think the knock-on effect for the UN is going to be very significant.

I think the UN is not particularly well-prepared for it, in the sense that it had taken European civic-mindedness at the international level for granted. There’s a widespread hope that this is just a blip, but I fear that Europe’s internally-driven preoccupations will last at least a few years. And whether European money then returns to the UN or not is impossible to predict.

We’re at a meeting right now in which we’re talking about regional organizations among other things, and one of the points being made is how very different they are each from the other. I wanted to ask you about three or four of them. The first is the African Union, how it’s evolved and what it is now; the second is the Organization of American States, an organization, frankly, you don’t hear that much about anymore; and the third one I want to ask you about because you are now living in Asia is ASEAN—whether the image of ASEAN has gone through a change?

The African Union is an outgrowth of the Organization of African Unity, and it was pretty ineffective. To their credit, the Africans decided to effect a reset, creating a different organization with much greater authority, with more credible decision-making bodies, notably the Commission of the African Union. Perhaps because there have been so many conflicts in Africa, the organization has focused primarily on peace and security. It’s done so much better than many analysts would have predicted—it’s been pretty consistent.

The Commission has had strong leadership pretty well throughout its history; the very strong Mrs. Zuma at the moment. It’s buttressed also by some strong sub-regional organizations, notably ECOWAS in West Africa. African institutions have been able to address a number of African conflicts credibly.

Their biggest problems are capability, military, and finances. The outside world has been able to help with finances, often by “re-hatting” what were originally African Union efforts, emergency efforts, as UN peace operations. That took the financial pressure off the African Union, but also by supporting the African Union’s political impulses on these conflicts.

The Organization of American States is nearly the reverse. It flirted with the idea of a significant role in peace and security in the Americas when it tackled the interlocking civil wars of Central America about 25 years ago. But ultimately, the DNA of most Latin American countries, South American countries particularly, is one of non-intervention militarily in the affairs of others.

They had so many wars early on in Latin America’s history that ultimately they shy away from the use of force as a means to address peacebuilding. One exception has been Haiti, where a number of Latin American countries have played an important role for the UN and for the OAS, including Brazil. So the OAS doesn’t attract much attention to itself.

As a Canadian citizen, and thus through my country a member of the Organization of American States, I would like it to effect a reset at some point and become really effective at something or other, because it’s costing the taxpayers of the Americas money. And if you’re taking taxpayers’ money, you should have something to show for it. And perhaps its vocation will be, as it seemed to be 20 years ago, in the area of the construction of democracy, because that’s what most Latin Americans can agree on.

ASEAN is an interesting organization because it was derided for so long in the West and particularly in the geostrategic community, as a useless talk shop. And it’s still sometimes described dismissively as a talk shop, but actually most people have come around to the view that talking is quite useful, especially compared to the alternatives.

Now we see all these geostrategic geniuses stampeding to Singapore every year to attend the Shangri-La Dialogue, which is the ultimate expression of the ASEAN approach to talking about problems rather than making them worse. So I think, in a way, ASEAN has the satisfaction of knowing that the regional preference in terms of how to deal with incipient conflict or actual conflict has won over many new adherents and that Asian ways of doing things are being recognized today as perfectly well-suited to Asia.

NGOs and civil society: those two words are always uttered with a certain sanctified sound around the UN. I mentioned a moment ago that you can sort of hear the sound of an organ chord playing when people talk about them. The UN obviously must partner with such organizations, but should it be careful how it does it?

These organizations are a very large part of the real world. The UN lives in a bubble in many ways, and the real world is out there with all sorts of different constituents, good, bad, and indifferent. In business and in the NGO world as well, you have a mix of the good, the bad, the indifferent.

Of course, the UN needs to engage with the real world across the board, but be selective with who it lends its own credibility to. The UN has credibility and just conferring it without thought or knowledge on all comers would be a reputational mistake. So should it be careful? Yes. Should it engage energetically? Yes.

Finally, you, who know the UN so well, are now living in Asia and seeing it from a certain distance and might have a new perspective on some aspect of it. We tend to be very critical of the UN, particularly in the United States and somewhat in Europe. Are you hearing from other people—from where you’re living now and people you’re talking to—that maybe the UN has greater value at some distance from there than it does here?

Yes, I think particularly it has value—perceived value—to people in the developing world. They still repose great faith in the UN, in its ideals, and also what they perceive to be its effectiveness in development. In a sense, in embodying values they would like to see their own countries adopt not just in theory, but in practice. So it’s a mix, I think, of all of these impulses and others.

But definitely in the developing world, there’s a much more positive view of the UN than there is in the industrialized world. Now in the industrialized world, there may be reasons for the slightly more negative view and those reasons may be that the UN has been paid for by the industrialized world very largely.

Once the developing world starts paying for the UN more than it has in the past, it also may become more critical. So I think the world changes, perceptions of the UN change. When developing countries start paying more of the UN bill, which a number of them are very open to doing—in fact, some Western countries are the ones who are hesitant about losing their financial weight in international institutions—it may be that developing countries will become more demanding. They will want more value for their money, the way the US has often complained about not getting sufficient value for its money. But at the moment, the constituency for the UN is definitely the developing world, civil society at large all over the world.